It’s a quiet afternoon in a park in Xi’an, not a long way from the silent, imposing terracotta military guarding China’s first emperor. But right here, the air is packed with laughter. A group of young Chinese college students, at the side of a few curious tourists, are kicking a feather-filled ball between them, their feet moving with a surprising dexterity. They aren’t playing soccer as we understand it; they may be carrying out Cuju, a historic sport with records stretching back over two millennia. This scene, a part of a cultural revival, is more than just a nostalgic activity. It is a residing portal to a forgotten international of play, a world where China becomes not just an economic and philosophical chief, but a powerhouse of innovation in undertaking and recreation.

For centuries, the history of world games has been predominantly Eurocentric. We write of the Olympic roots in Greece, the Roman gladiatorial games, and the medieval jousts of Europe. But even as this was happening, and indeed sometimes beforehand, in the courtyards and courts of medieval China, a refined culture of play was in bloom. These were not childish amusements; they were military training aids, means of philosophical communication, and finely detailed social rituals. Cuju (medieval football) and Jǔdòu (medieval tabletop strategy) are more than footnotes to history. They are cornerstones to grasping an integrated Chinese worldview, and their reverberations, no matter how subtle, can be heard in some of the globe’s most popular diversions today. This is an odyssey to reclaim these lost games, to learn their rules and their cultural significance, and to unravel the subtle but intriguing threads that bind them to the world playground.

The Philosophical Playground: Why Games Mattered in Ancient China

To appreciate ancient Chinese games, one should first leave behind the Western modern dichotomy that tends to divide work from play, or seriousness from frivolity. In premodern Chinese thought, especially under the spell of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism, activities were intricately entwined. Played was never just a game.

Confucianism and Social Order: For the Confucian scholar-official, play represented a microcosm of the ideal society. Strategy games, such as Liubo or Go (Weiqi), instructed respect for hierarchy, the merits of foresight, and the virtues of ritualized behavior. Victory through sheer force was less desirable than victory through greater strategy and virtue, recapitulating the Confucian ideal of the virtuous ruler.

Daoism and Natural Flow: Daoist philosophy stressed harmony with the natural, effortless motion of the world, wu wei. The philosophy is starkly alive in physical sports such as Cuju or the internal martial arts. It was not about overpowering one’s opponent through muscle but moving in a flowing, economical sense of motion, going with the flow of the game itself. The rotating, feather-filled ball in Cuju was an ideal object to practice tracking and directing, not forcing.

Buddhism and Mental Discipline: Games were an ideal arena for mind training. The deep concentration needed for an extended game of Go was similar to meditation, developing patience, concentration, and detachment from instant emotional responses to wins and losses.

This philosophical foundation ensured that game-playing was an honored, indeed a necessary, pursuit for all, from the emperor to the humblest farmer. It was a method of building the self, learning the world, and uniting with the community.

Jǔdòu: The “Fight Bean” Game – A Precursor to Global Strategy

Long before the world was familiar with Chess, or even Go in its modern guise, existed Jǔdòu, whose name means whimsically “fight bean” or “throwing beans.” Sounds basic, even primitive. Yet the game was a captivating mixture of luck, strategy, and corporeal skill that engaged the minds of Han Dynasty aristocrats (206 BCE – 220 CE).

Imagine a small, lacquered wooden board, intricately decorated with symbols. Instead of pieces, players would use actual beans, seeds, or small stones. The game’s mechanics are not fully preserved in a single rulebook, but through archaeological finds—like exquisitely crafted boards found in tombs—and scattered textual references, historians have pieced together a plausible reconstruction.

The Gameplay of Jǔdòu:

The board itself usually had a specific shape, frequently with some central square or circle and radiating paths of various sorts. Players would turn up on their turn some beans or sticks on the board. Where they landed—how far and in what direction from the markings and symbols—would control the player’s “pieces” (the beans themselves or perhaps separate markers) to move. This aspect rendered it a game of luck, much like the dice roll in Backgammon.

But the strategy came next. Based on the “throw,” a player could move their pieces, with the objective likely being to capture an opponent’s pieces or reach a specific goal. This combination of randomized bean-throwing mechanics and subsequent tactical movement created a unique dynamic. It was a physical and mental dance between accepting the hand dealt by fate (a very Daoist concept) and using one’s wit to maximize the opportunity.

Cultural Significance and Evolution:

Jǔdòu was more than a parlour game. It was a popular Han Dynasty board game recreation for the aristocracy. It reflected a world where fate and strategy were intertwined in daily life, from the battlefield to the imperial court. A scholar could be the most brilliant strategist, but without the favor of the emperor (an element of chance), his plans could come to naught. Jǔdòu embodied this reality.

Over time, the physical, “chaotic” element of throwing beans may have been seen as less refined. The game probably evolved, with the randomizer becoming more formalized (such as the six-sided rods of the game Liubo) and ultimately giving way to strictly strategic games like Go, which excluded chance altogether, favoring sheer brainpower. Jǔdòu is therefore a vital missing link in the board game history, a testament to an experimental period in which the boundaries between divination, chance, and strategy were expertly blurred. Its influence isn’t a direct ancestorship to some contemporary game, but conceptual: the mix of luck and skill that we find in so many tabletop games today.

Cuju: The Emperor’s Football and Its Journey West

If Jǔdòu is the intellectual aspect of Chinese play, then Cuju is its exciting, physical pulse. Cuju (蹴鞠) literally means “kick ball.” And although the name is plain, the game evolved into a highly advanced and diverse sport with a recorded history dating back more than 2,000 years.

The Origins and the Military Connection:

The oldest credible records of Cuju are found in the Zhan Guo Ce (“Strategies of the Warring States”), a 3rd-century BCE text.

It portrays Cuju as not a recreational activity but a critical method of Warring States-era military training. Troops used to kick around a heavy leather ball for developing their strength, agility, and balance—attributes crucial for both foot soldiers and cavalrymen. This etymology is similar to that of most Western sports, such as the Roman harpastum or medieval mob football, which also originated as military training.

The Rules of the Game: Two Distinct Styles:

Cuju developed two primary forms, much like the way present-day rugby and soccer are separate branches from the identical trunk.

Zhu Qiu (Chasing the Ball): This was the competitive, team-based version of Cuju. It was often played on a large field, sometimes within the confines of the imperial palace. Two teams, separated by a central line, would strive to kick the ball through an opening in a net. This net was suspended high on poles, a target remarkably similar to a soccer goal, but much smaller and elevated, requiring immense precision. This format was a spectacular public spectacle, especially during the Tang (618-907 CE) and Song (960-1279 CE) dynasties. Historical texts describe matches attended by emperors, with professional players achieving celebrity status.

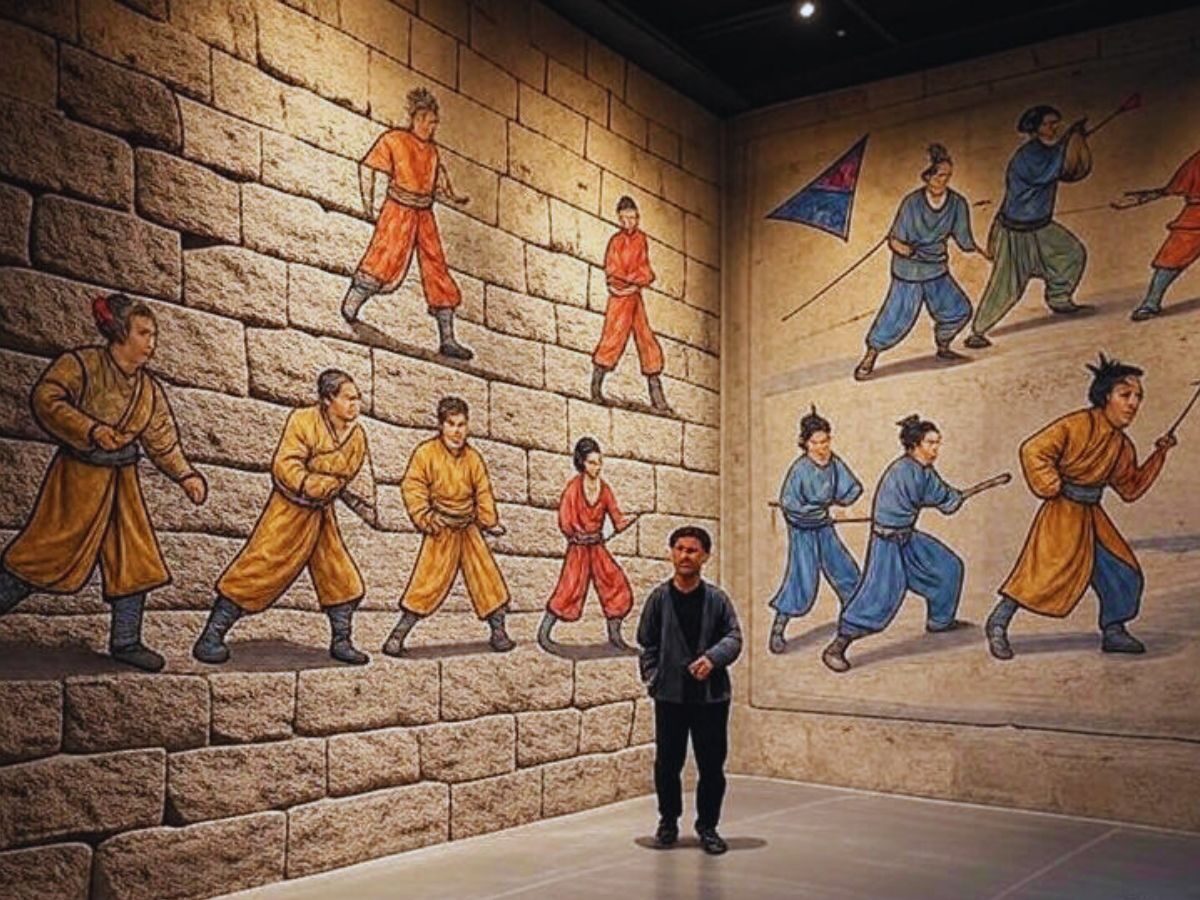

Bai Da (White Kick): This was the artistic, performance-oriented version of Cuju. Here, the goal was not to beat an opponent, but to demonstrate supreme individual skill. Players would stand in a circle (a Cuju kicking circle formation) and keep the ball airborne using only their feet, knees, shoulders, and head—but never the hands. The difficulty was staggering. The “white kick” referred to the scoring method; for every successful kick without the ball touching the ground, a player would earn a point, often marked by a stick or a flower being placed in a vase. This was Cuju as a performance of wu wei—effortless grace and control. It was the preferred version for aristocrats and women, who formed their own Cuju teams for women in ancient China.

The Cultural Peak and the Silk Road Connection:

The Song Dynasty was the golden age of Cuju. The sport became thoroughly professionalized. Song Dynasty urban entertainment hubs in cities like Kaifeng and Hangzhou featured commercial Cuju clubs, such as the famous “Round Eagle” club. These clubs had full-time players, managers, and even youth academies. This level of organization for a ball game was unprecedented in the world at that time.

This was also the period of peak Silk Road activity. While no “smoking gun” file asserts “Cuju changed into soccer and was exported to England to turn out to be soccer,” the pathways for cultural exchange have been wide open. Arab and Persian merchants, who had substantial contact with Song China, would have surely witnessed this charming game. It is fantastically possible that descriptions, or at least the concept of a recreation targeted on kicking a ball, traveled along those trade routes, subsequently filtering into the Mediterranean and Europe. The idea should have stimulated the improvement of neighborhood ball video games, acting as a catalyst instead of an immediate ancestor. This Cuju Silk Road transmission theory remains a compelling, though debated, area of historical study.

Beyond Cuju and Jǔdòu: A Panorama of Play

To focus only on these two games is to miss the rich tapestry of ancient Chinese recreation. The playground was vast and varied.

Qiulin Xi (Go): While Go originated earlier, it was during the Tang and Song dynasties that it became the preeminent game of intellectual pursuit, the “game of kings.” Its profound complexity and reflection of cosmic principles made it the ultimate test of strategic mind.

Chinese Archery Games: Archery changed into one of the six noble arts of historic China. Beyond army use, it changed into a ceremonial and aggressive game, with contests that specialize in precision, ritual, and form, deeply infused with Confucian ideals of propriety.

Ancient Chinese Board Games like Liubo: Pre-dating Even Jǔdòu and Liubo became complicated race recreations involving dice, tokens, and a distinct board. It became immensely popular for centuries before fading into obscurity, a ghost in the archaeological report.

Kite Flying and Top Spinning: These were now not simply kids’ games but fairly developed personal pursuits. Kite flying had spiritual and army applications (signaling), while pinnacle spinning involved elaborate tricks and competitions, and the use of tops crafted from wood, bamboo, or even high-priced ivory.

The Fading Echoes: Why Were These Games Forgotten?

If these video games had been so deeply embedded in Chinese tradition, why did they refuse? The reasons are complex and intertwined with China’s turbulent history.

The Mongol Invasion (Yuan Dynasty): The conquest through Kublai Khan within the thirteenth century disrupted the sophisticated city tradition of the Song Dynasty. The professional Cuju clubs, dependent on a stable, wealthy urban merchant class, likely disintegrated.

The Ming and Qing Dynasties’ Conservatism: The later imperial dynasties have become more and more inward-looking and conservative. The intellectual magnificence, stimulated by a strict Neo-Confucianism, frequently viewed vigorous physical activities like Cuju as unrefined and frivolous. The attention shifted heavily toward scholarly interests like calligraphy, painting, and poetry.

The Cultural Trauma of the 19th and 20th Centuries: The “Century of Humiliation” at the hands of Western powers and Japan brought about a profound countrywide self-examination. In the hunt to modernize and make the state stronger, many conventional practices were discarded as symbols of a weak, old past. When contemporary Western sports like football and basketball were introduced, they were embraced as a part of a new, modern identification, inadvertently pushing native sports like Cuju into near-total obscurity.

The Modern Revival: Archaeology, Video Games, and Cultural Pride

The story doesn’t end in oblivion. The last few years have seen an awesome resurgence of hobbies in China’s conventional games, pushed by means of numerous factors.

Archaeological Discoveries: The commencing of tombs, like the Mawangdui Han tomb, has yielded extraordinarily well-preserved recreation forums, portions, and even texts describing policies. These revelations have moved those games from the realm of fable into tangible history.

Government-Led Cultural Promotion: As China’s international stature has grown, so has its preference to reclaim and promote its cultural and historical past. Cuju, especially, has been championed as a symbol of ancient Chinese innovation. Demonstrations are now common at cultural festivals, and the metropolis of Linzi, considered the birthplace of Cuju, has constructed a museum devoted to the game.

The Digital Gateway: This is perhaps the most powerful engine of revival. Historical Chinese games in video games have become a phenomenal success. Titles like Total War: Three Kingdoms incorporate elements of the era’s culture. More directly, games from Chinese developers often feature characters playing Go or even Cuju minigames. This exposes a global audience to these ancient pastimes in an interactive, engaging way, creating a “Cuju digital heritage revival” that books alone could never achieve. A player in Berlin or Boston can now, virtually, experience the challenge of keeping a feather-stuffed ball airborne.

This revival is not about rejecting global sports but about adding depth to China’s cultural identity. It’s an understanding that before the world embraced soccer, China had already perfected the art of the kick.

Conclusion: Not Just a Game, But a Worldview

The journey from the bean-throwing strategists of the Han Dynasty to the graceful kickers of the Song court is more than an antiquarian’s curiosity. It is a vital correction to a narrow historical narrative. The story of global play is not a straight line from Greece to Rome to Europe. It is a sprawling, interconnected web, and China holds several of its most vibrant threads.

Rediscovering games like Jǔdòu and Cuju is to rediscover a facet of the Chinese soul. It reveals a culture that saw physical activity as philosophy in motion, and strategy as a way to understand the cosmos. The silent, focused tension of a Go board and the aerial ballet of a Cuju ball are two expressions of the same principle: that play is a fundamental human language for exploring balance, skill, and our place in the world.

The next time you see a soccer match, or ponder a move on a chessboard, consider the possibility of deeper, older echoes. Perhaps, in the arc of a perfectly placed cross, there is a faint memory of a Song Dynasty performer keeping a feather ball aloft for an admiring crowd. The games of ancient China are not entirely forgotten; they are simply waiting for us to listen more closely to their enduring, playful whispers

+ There are no comments

Add yours