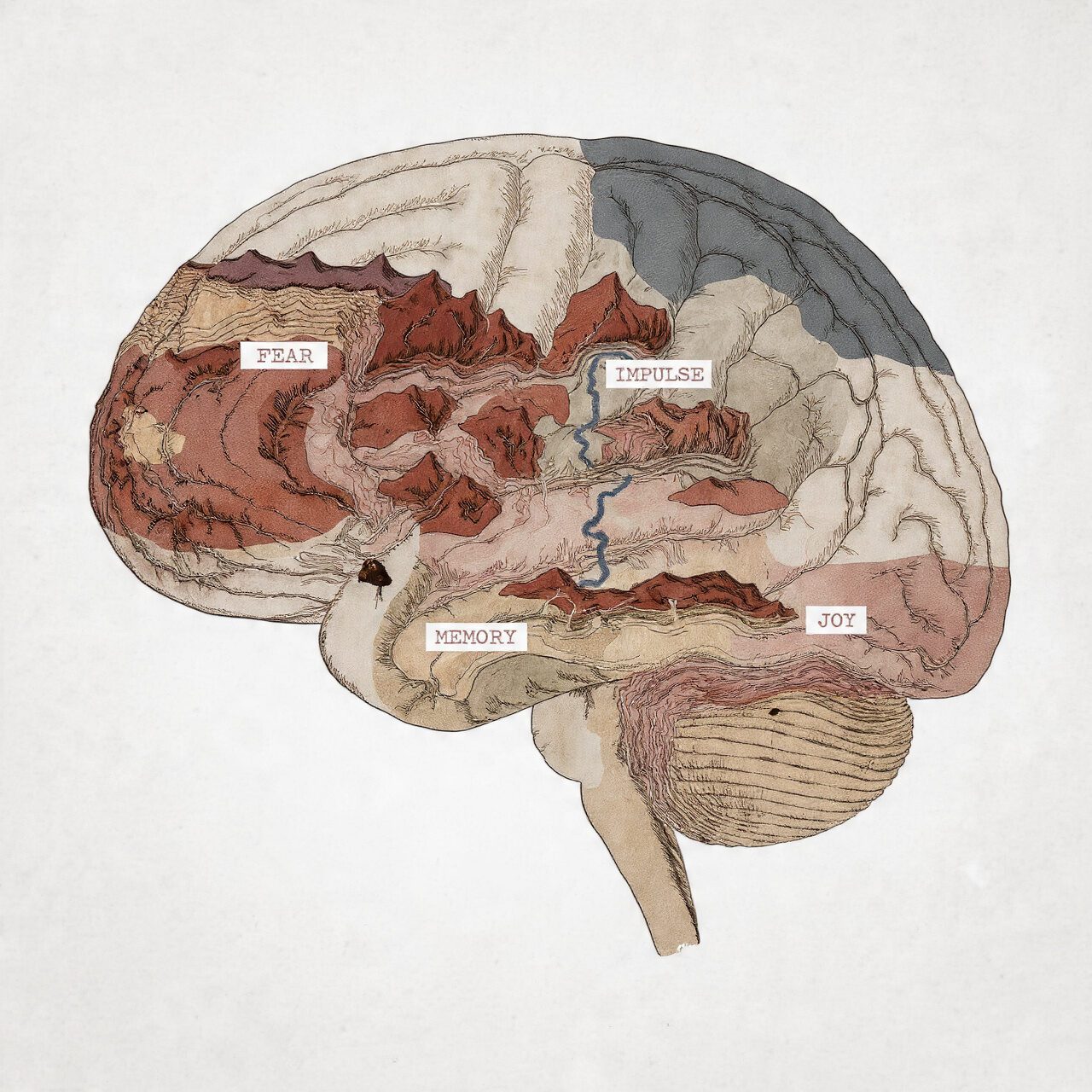

I have heard the equally determined sentence phrased in a thousand exceptional approaches: “Doctor, what’s wrong with me?” It’s a query brimming with worry, shame, and a deep longing for clarity. In that second, the vague, stigmatizing label of “mental trouble” is fully useless. It offers no direction, no solace, no route forward.

The adventure from that terrifying question to a significant solution is the essence of clinical diagnosis. And it starts off evolved through dismantling the monolithic idea of “intellectual infection” and appreciating the great, nuanced landscape of human psychological suffering. So, how many issues are there? The easy, numerical solution is over 300 distinct mental issues cataloged within the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR), the number one manual for clinicians in the United States. The World Health Organization’s ICD-11, used globally, lists a similar range.

But to forestall at that range is to overlook the entire factor. It’s like being instructed that an incredible library contains 300 books; the fee isn’t inside the count, however, but within the tales, the genres, and the expertise within. My long time of practice has taught me that this catalog isn’t about slapping a label on a person. It’s about mapping a personalized route out of suffering. Today, I want to be your guide through this complex taxonomy, explaining not just the “how many,” but the “why” and “so what” of it all.

The Frameworks: DSM and ICD – Not Bibles, But Evolving Maps

First, we must understand the tools of the trade. In general medicine, a diagnosis is often confirmed by a blood test, an X-ray, or a biopsy—a tangible, biological marker. In psychiatry and clinical psychology, for most conditions, we lack such definitive tests. Instead, we rely on meticulously developed diagnostic frameworks based on observed clusters of symptoms, their duration, and the level of distress or impairment they cause.

The two main systems are:

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR): Published by the American Psychiatric Association, this is the foundational textual content for most clinicians in North America and influential globally. It is categorical, which means it defines problems as awesome scientific syndromes.

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11): Published by way of the World Health Organization, which is the world’s popular source for health reporting and, in many countries, medical prognosis. Its mental health chapter aligns significantly with the DSM, but is structured for worldwide epidemiological and health system use.

I actually have labored through multiple variants of these manuals. I recollect the transition from DSM-IV to DSM-5—the heated debates in journals, the shifts in knowledge that moved situations from one bankruptcy to another (like OCD leaving the tension issues bankruptcy). These manuals are living files, imperfect but constantly refined through new studies and medical knowledge. They are not carved in stone; they’re the best collective map we’ve got for a terrifyingly complex territory.

A Tour of the Landscape: The Major Categories of Disorder

To grasp the diversity, let’s walk through the primary chapters of the DSM-5-TR. This is where the generic term “mental problem” completely shatters into meaningful, specific pieces.

1. Neurodevelopmental Disorders

These conditions have their onset in the early developmental period. They represent disruptions to the typical trajectory of brain maturation.

Intellectual Disabilities

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): Characterized by persistent differences in social communication and interaction, alongside restricted, repetitive patterns of behavior or interests.

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): A pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity-impulsivity that interferes with functioning or development.

Specific Learning Disorders: Such as dyslexia.

The Clinical Reality: Early in my career, I saw children branded as “difficult” or “slow.” An accurate analysis of ASD or ADHD isn’t about restricting a child with a label; it’s about unlocking the right kind of assistance. It adjusts the question from “Why won’t you behave?” to “How does your mind work, and how are we able to help you thrive?” The difference is everything.

2. Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders

This category is defined with the aid of fundamental disturbances in reality testing—thinking, belief, and behavior that have lost touch with consensus fact. Key functions include hallucinations, delusions, disorganized thinking and speech, and negative symptoms like diminished emotional expression.

Schizophrenia

Schizoaffective Disorder

Delusional Disorder

The Clinical Reality: The public stigma is massive and cruel. I certainly have treated individuals with schizophrenia who, with regular, compassionate care regarding antipsychotic treatment and psychosocial remedy, control their signs and symptoms, preserve jobs, and have rich internal lives. The goal is not some Hollywood “cure,” but stability, insight, and quality of life. They are not their diagnosis.

3. Bipolar and Related Disorders

These are described through dramatic, frequently debilitating, shifts in mood, strength, and interest degrees, biking among poles.

Bipolar I Disorder: Defined through manic episodes that last for a minimum of 7 days, frequently with depressive episodes.

Bipolar II Disorder: A pattern of hypomanic episodes (much less severe than full mania) and fundamental depressive episodes.

The Clinical Reality: This is a critical example of why precision matters. I have seen patients misdiagnosed for years with “just depression.” Prescribing a standard antidepressant to someone with undiagnosed Bipolar II can trigger a devastating manic or hypomanic episode. Distinguishing between unipolar depression and bipolar disorder is not academic; it’s a critical safety issue.

4. Depressive Disorders

The center characteristic is a persistent, pervasive sad, empty, or irritable mood, observed by way of the use of somatic and cognitive adjustments that substantially impair functioning.

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD): The classic episodic depression.

Persistent Depressive Disorder (Dysthymia): A continual, lower-grade but enduring despair.

Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD): A severe, cyclical temper disorder associated with the menstrual cycle.

The Clinical Reality: The word “I’m depressed” in regular language is almost out of place, which means that. Clinical depression is not sadness. It is a neurological state of shutdown—an absence of feeling, motivation, and hope. Treatment isn’t about “cheering up”; it’s about slowly reactivating the brain’s reward and motivation systems, sometimes neuron by neuron.

5. Anxiety Disorders

The most commonplace category of intellectual problems, united through excessive worry and tension, but differentiated by the focal point of that worry.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD): Chronic, “free-floating” fear approximately ordinary things.

Panic Disorder: Recurrent, unexpected panic attacks and the fear of them.

Social Anxiety Disorder: Intense fear of social or performance situations.

Specific Phobias: Irrational fear of a discrete object or situation.

The Clinical Reality: An affected person within the throes of a panic assault is frequently convinced they may be dying. Their body is in complete “combat-or-flight” mode. Part of my work is psychoeducation: supporting them to understand this is a misfired survival alarm, not a coronary heart attack. Then, we work on retraining the alarm machine through therapy.

6. Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders

This institution, now rightly separated from tension problems, involves intrusive thoughts and repetitive behaviors.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD): The cycle of obsessions (intrusive, unwanted thoughts) and compulsions (repetitive behaviors to neutralize the anxiety).

Body Dysmorphic Disorder: Preoccupation with perceived flaws in appearance.

Hoarding Disorder

The Clinical Reality: People with OCD regularly have profound perception—they understand their compulsions are irrational; however, the anxiety feels viscerally, overwhelmingly actual. Telling them to “simply forestall” is like telling a person with a damaged leg to “just walk.” Treatment requires specialised cures like Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP) to interrupt the neural habit loop.

7. Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders

This class explicitly links the ailment to a previous demanding or demanding occasion, a critical validation for survivors.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Acute Stress Disorder

Adjustment Disorders

The Clinical Reality: Trauma doesn’t simply stay within the memory; it lives inside the frame. The hypervigilance, the startle response, and the dissociation—these are survival adaptations that have emerged as maladaptive. Treatment often has to cope with this somatic thing, through remedies like EMDR or somatic experiencing, to assist the autonomic nervous system in the end to feel safe.

8. Dissociative Disorders

A disruption in the normal integration of consciousness, memory, identity, or perception.

Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID): The presence of two or more distinct personality states.

Dissociative Amnesia

The Clinical Reality: These are often adaptive responses to unbearable, early childhood trauma. The mind fractures to survive. Therapy is not about “getting rid” of parts, but about facilitating communication, cooperation, and integration among them to help the whole person function.

9. Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders

Psychological distress that manifests primarily through physical symptoms.

Somatic Symptom Disorder

Illness Anxiety Disorder

The Clinical Reality: The cardinal error here is to say, “It’s all in your head.” The ache, the fatigue, the GI distress—it is actual and felt inside the frame. The work is to assist the affected person in understanding the profound mind-frame connection and how continual strain and emotional pain can dysregulate the autonomic nervous system and create physical signs and symptoms.

The Critical Complexities: Why the Number is Just a Starting Point

If diagnosis were as simple as matching a checklist to one of 300 boxes, my job would be automated. The profound complexity lies in the following realities:

Comorbidity is the Rule, Not the Exception. It is far more common for a person to meet criteria for multiple disorders than for just one. Depression and anxiety are frequent partners. PTSD often co-occurs with substance use. This isn’t diagnostic sloppiness; it reflects the interconnectedness of our brain systems. A dysregulated fear circuit can gaslight tension, disrupt sleep, and contribute to depression. I treat people, not isolated diagnoses.

The Spectrum Model. We increasingly understand disorders as existing on spectrums. Autism Spectrum Disorder is the clearest example. This recognizes that signs exist on a continuum of severity and presentation. There is no brilliant line between sizeable shyness and Social Anxiety Disorder. This version reduces stigma and allows for early intervention.

The Dimensional Perspective. The DSM is categorical: you have MDD, or you don’t. But human experience is dimensional. We all experience anxiety, sadness, and focus issues. Mental disorders represent the extreme, pathological end of these natural human dimensions. A good clinician always holds this in mind to avoid pathologizing normal human variation.

Cultural Formulation. The DSM includes an essential appendix on this. What is a psychotic symptom in one cultural context may be a normative spiritual experience in another. Symptoms are expressed and experienced through the lens of culture. A competent diagnosis must account for this.

The Heart of the Matter: Why This Precision is an Act of Compassion

After these kinds of years, I see the diagnostic manual no longer as an e-book of labels but as a device for communication, a guide for compassion, and a roadmap for recovery.

It Directs Effective Treatment: This is paramount. The evidence-based treatment for OCD (ERP) is fundamentally different from that for Bipolar I (mood stabilizers), which is different from trauma therapy for PTSD. An accurate diagnosis is the first step on the correct path.

It Validates Suffering: For a person who has been told to “get over it” or “attempt harder,” receiving a clean, established diagnosis may be profoundly validating. It means, “Your suffering is actual, it has a call, it’s understood, and you are not on your own.”

It Fosters Hope and Agency: With a diagnosis comes understanding. With expertise comes the power to search for specific resources, hook up with others who recognize, and song progress in a significant manner.

It Provides a Common Language: It allows me to speak genuinely with a purchaser’s medical doctor, with their family (with permission), and with the purchaser themselves, demystifying their experience.

Conclusion: From a Number to a Narrative

So, how many mental disorders exist? Over 300. But the true answer is more profound. There are hundreds of recognized, studied patterns of human psychological suffering. This number reflects the breathtaking complexity of the human mind and the myriad ways its balance can be disrupted.

If you take one thing from this, let it be this: Dismissing your struggle or a loved one’s struggle as just a “mental problem” is a dead end. The adventure in the direction of recovery begins with curiosity, not stigma, and with precision, not generalization. Seeking a certified professional who allows you to apprehend your precise experience within this nuanced landscape is an act of courage. It is the primary and maximum vital step in writing a brand new, healthier bankruptcy in your story. The specificity of the map is what makes the journey out of the desert viable.

+ There are no comments

Add yours