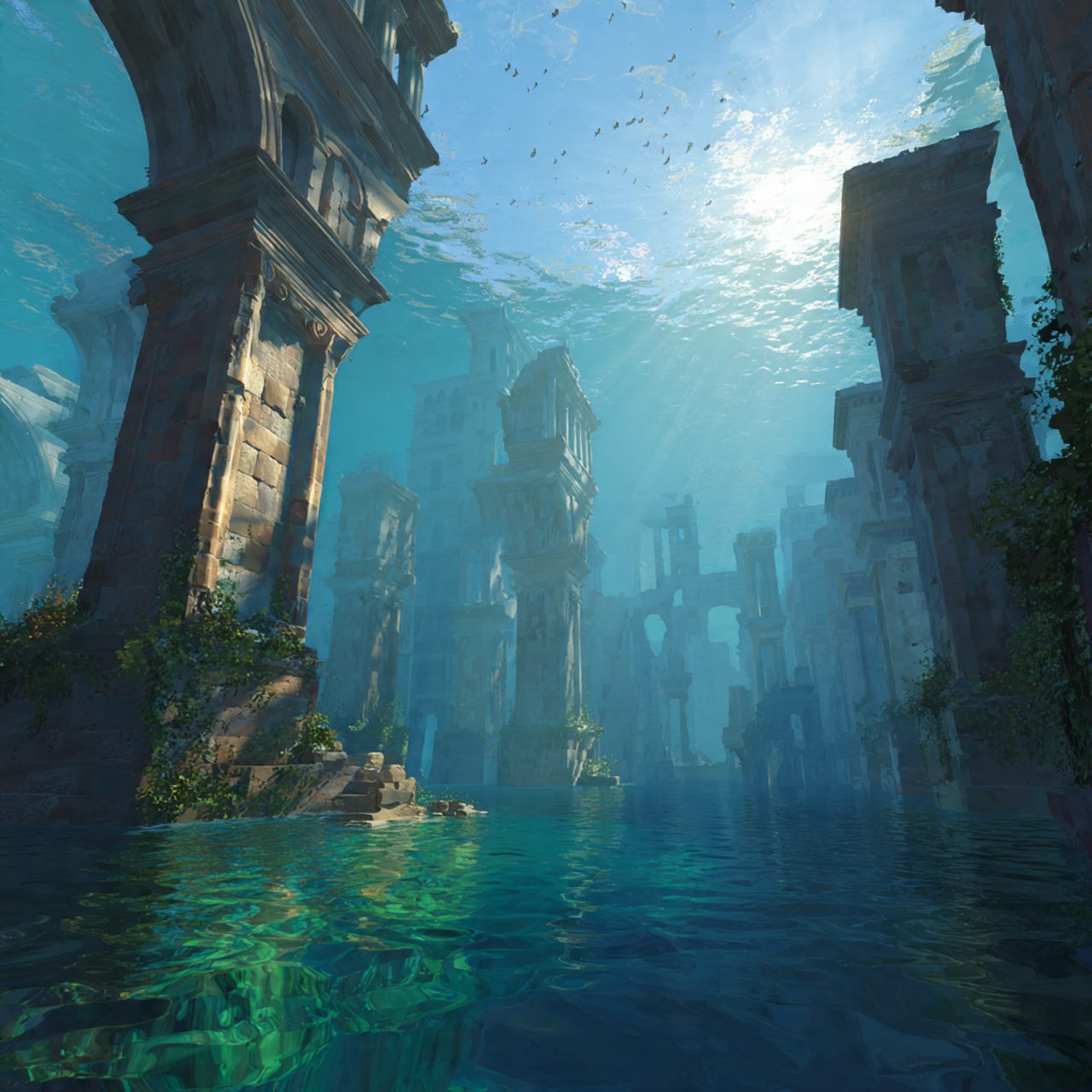

We’ve all felt the pull. The photo is iconic: gleaming spires of an imposing city, misplaced underneath the waves, holding secrets and techniques of advanced generation and awareness beyond our own. From Plato’s authentic dialogues to blockbuster films and video games, the story of Atlantis is arguably the sector’s most persistent and captivating myth. But it’s miles away from me. It is the flagship of a good-sized fleet of sunken continents, vanished empires, and forgotten golden ages from long ago—Lemuria, Mu, Hyperborea, and more—that sail without end through our collective creativeness.

This enduring fascination is more than a mere hobby; it’s a profound cultural and psychological phenomenon. Why, in an age of satellite TV for PC mapping and deep-sea submersibles, does the dream of a lost global hold such power? What is it about those testimonies that resonates throughout centuries, adapting to every new technology from the Age of Exploration to the Space Age? This article will dive into the depths of what we might call the “Atlantis Complex.” We will discover its philosophical birth, decode the mind science behind its enchantment, map its sibling myths, examine its contemporary pseudo-archaeological forms, and confront its real-world effects. Ultimately, we’ll find out that our obsession with out-of-place civilizations is a lot less about records and more about protecting a replica of our personal hopes, fears, and the eternal question: who are we, and where did we come from?

1. The Original Blueprint – Plato’s Atlantis and the Birth of a Myth

The first important step in knowing the Atlantis Complex is to return to the source. Contrary to famous belief, Atlantis isn’t always an ancient, global folk fantasy passed down through millennia. It is a tale with a single, identifiable writer and a specific motive.

1.1 Plato’s Dialogues: Not History, But Allegory

The story of Atlantis appears completely in Plato’s later dialogues, Timaeus and the unfinished Critias, written around 360 BCE. The story is presented as a conversation. Critias recounts a story told to his ancestor, Solon, by Egyptian priests: an effective, technologically state-of-the-art island empire placed beyond the “Pillars of Hercules” (the Strait of Gibraltar). Atlantis changed into a paragon of civilization, with concentric rings of land and water, a stunning structure, and a rich, noble society. However, over the years, people have ended up corrupted by greed and pleasure. As punishment, the gods dispatched “violent earthquakes and floods,” and in “a single day and night of misfortune,” the island was swallowed by the sea and vanished.

It is critical to observe the context. Plato was now not a historian; he was a logician. He used testimonies—what students name mythoi—as cars for his ideas. In the dialogues, Atlantis is juxtaposed with an idealized Athens, which defeats the aggressive Atlanteans. The entire narrative serves as an ethical and political allegory about the corruption of power, the correct country, and divine retribution. For Plato, Atlantis serves as a plot device, a fictional counterpoint that illustrates a philosophical lesson about hubris and justice.

1.2 From Philosophical Tool to “Lost History.”

So how did a philosophical allegory become the target of countless historical expeditions? The transformation began centuries after Plato. Early philosophers like Aristotle dismissed Atlantis as an invention; others, like the historian Plutarch, began to treat it more ambiguously. The crucial shift occurred in modern technology, especially in the 19th century, with the paintings of the American congressman and pseudo-historian Ignatius Donnelly.

In his 1882 ebook Atlantis: The Antediluvian World, Donnelly argued that Plato’s story changed into the literal reality. He posited Atlantis as the mom civilization from which all ancient cultures (Egyptian, Mayan, and so forth) sprang, explaining perceived similarities in myths and monuments. Donnelly’s paintings became a masterpiece of speculative synthesis, mixing selective evidence with grand conjecture. It changed Plato’s moral fable with a sweeping, romantic ancient thesis. This act of re-contextualization—taking a tale from one style (philosophy) and placing it in another (records)—is the foundational act of the cutting-edge Atlantis Complex. The seed of allegory was planted, and it grew right into a tangled wooded area of literal belief.

2. The Psychological Depths – Why Our Brains Love a Lost World

The story’s starting place explains its entry into culture; however, it no longer has its tenacious grip on our psyche. For that, we must peer inward, to the cognitive and emotional wiring that makes the idea of a misplaced golden age so profoundly gratifying.

2.1 The Lure of a Golden Age and Nostalgia for a Past That Never Was

Humans are creatures of narrative, and one of our most effective narratives is that of decline. The delusion of a Golden Age—a time when human beings had been wiser, society turned into just, and generation become in concord with nature—is a near-universal archetype, from Hesiod’s Five Ages of Man to the Biblical Garden of Eden. Atlantis fits this pattern perfectly. It offers an imaginative and prescient view of ancestral glory, a background we have in some way fallen from. This taps right into a deep-seated “chronological snobbery,” however, in the opposite: a perception that the beyond became superior to the prevailing. It’s a comforting shape of nostalgia for a home we in no way simply knew, supplying a sense of roots and meaning in a chaotic, contemporary world.

2.2 Filling the Gaps: Pattern Recognition and Cognitive Closure

The human brain is a pattern-recognition machine, and it despises a vacuum. History and archaeology are full of gaps, mysteries, and anomalies: How were the pyramids built? Why do similar flood myths appear worldwide? What explains this advanced ancient artifact?

A lost civilization like Atlantis offers a one-stop shop solution. It provides cognitive closure, a neat and dramatic answer to multiple, disparate questions. Instead of dealing with the complex, incremental, and often unknown processes of real cultural diffusion and innovation, the mind can latch onto a single, elegant cause: a superior source culture. This “great explainer” theory is intellectually seductive because it simplifies complexity into a compelling story.

2.3 The Romantic Allure of Catastrophe

There is a plain drama in sudden, overall collapse. The Atlantis fantasy combines the pinnacle of success with the totality of destruction—a cataclysmic dichotomy. This is far more romantic and narratively tidy than the slow, grinding decline that characterizes most actual historic collapses (like the Roman Empire). A single “day and night” of destruction is easy, poetic, and absolute. It permits us to explore our fears of apocalypse—of climate alternate, battle, or asteroid effect—from the safe distance of a fictional past. It’s a controlled, interesting brush with oblivion.

3. Beyond Atlantis – A Map of Mythical Continents

Atlantis is the archetype, but the Atlantis Complex has spawned an entire geography of fantasy. These sibling myths often follow a similar lifecycle: a speculative scientific hypothesis is born, later dies in the scientific community, but is resurrected and transformed by mystical or pseudo-historical movements.

3.1 Lemuria and Mu: Theosophy’s Lost Homelands

In the 1860s, zoologist Philip Sclater proposed “Lemuria”—a hypothetical land bridge across the Indian Ocean—to explain the distribution of lemurs between Madagascar and India. When plate tectonics provided a better explanation, the scientific concept was abandoned. However, it was eagerly adopted by esoteric thinkers, most notably Helena Blavatsky, founder of Theosophy. In her 1888 book The Secret Doctrine, Blavatsky reimagined Lemuria as the home of the Third “Root Race” of humanity: giant, hermaphroditic, egg-laying beings with a third eye. Similarly, “Mu” (or “the Motherland”) was popularized by eccentric archaeologist Augustus Le Plongeon and later by writer James Churchward as a Pacific counterpart to Atlantis, a supposed cradle of civilization that sank. These myths served as spiritual homelands, providing origin stories for concepts of lost esoteric wisdom and ancient, advanced human races.

3.2 Hyperborea and Thule: Aryans in the Arctic

This demonstrates the darker capacity of the misplaced civilization trope. Hyperborea originated in Greek mythology as a great, sun-drenched land past the north wind. Thule turned into a likely real location, stated by using the Greek explorer Pytheas. Over centuries, these vague northern locales have been mystified. In the past, due to the 19th and early twentieth centuries, German occultists and völkisch nationalists fused them with emerging racial theories. They posited Hyperborea/Thule as the primordial place of origin of the Aryan race, a superhuman civilization delivered down by using ice. This delusion was quickly co-opted with the aid of the Nazi Ahnenerbe (Ancestral Heritage) research institute, which backed expeditions to find evidence. Here, the misplaced civilization fable becomes weaponized to fuel racist ideology and nationalist supremacy, displaying its risky ideological flexibility.

4. The Modern Hunters – Pseudoarchaeology and Ancient Aliens

The 20th and 21st centuries provided new lenses through which to view the old obsession. Pseudoarchaeology and the Ancient Astronaut Theory are the modern, media-savvy manifestations of the Atlantis Complex.

4.1 The Pseudoarchaeology Playbook: How Myths Are Sustained

Pseudoarchaeology doesn’t follow the clinical method (speculation, checking out, peer review). Instead, it employs a recognizable set of rhetorical tactics:

Selective Use of Evidence: Cherry-picking facts that help the principle even as ignoring the giant frame of evidence that contradicts it (e.G., focusing on one anomalous artifact even as dismissing its setup cultural context).

Argument from Ignorance: “We don’t recognise exactly how this changed into constructed, consequently it ought to have been Atlanteans/extraterrestrial beings.” This logical fallacy turns a lack of evidence for one rationalization into evidence for a preferred, individual clarification.

Technological Determinism: The assumption that historical peoples were incapable of super-engineering feats, which requires an outside, advanced force. It underestimates human ingenuity, persistence, and skill.

The “Suppressed Knowledge” Trope: Claiming that mainstream academia, governments, or museums are actively hiding the reality to protect the status quo. This frames the pseudoarchaeologist as a courageous rebel, making skepticism in their claims appear a part of the conspiracy.

4.2 The Ancient Astronaut Hypothesis: Atlantis 2.0

Swiss writer Erich von Däniken’s 1968 book Chariots of the Gods? Supercharged the lost civilization trope for the Space Age. The central premise: extraterrestrial visitors were the actual “superior misplaced civilization” that interacted with historic humans, giving them generations, beginning their religions, and building their monuments.

This is essentially the Atlantis Complex re-skinned. It serves the same psychological functions:

The Golden Age: The aliens are the superior, wiser ancestors.

The Great Explainer: It simplifies all ancient mysteries into one cause.

Catastrophe & Loss: The aliens left or abandoned us.

It adds a modern, technological sheen and shifts agency entirely away from human achievement. It’s a narrative of passive inheritance rather than active creation, which can be appealing but is ultimately disempowering to the rich tapestry of human cultural development.

5. The Real-World Impact: From Harmless Fun to Harmful Fictions

Our fascination with misplaced worlds isn’t always a victimless hobby. It exists on a spectrum, with sizeable consequences at each end.

5.1 Inspiration Engine: Fuel for Art, Literature, and Exploration

On the tremendous side, the myth has been an exquisite catalyst for creativity. It has inspired limitless works of fiction, from Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea and H.P. Lovecraft’s cosmic horror to Disney’s Atlantis: The Lost Empire, the Tomb Raider franchise, and Marvel’s Namor. The concept has also, ironically, driven actual exploration. The long search for Atlantis has led oceanographers and archaeologists to survey large areas of the seafloor, now and again yielding real, charming discoveries of sunken settlements, along with Doggerland inside the North Sea or historical towns off the coasts of India and Egypt. The fantasy continues the spirit of exploration alive.

5.2 The Dark Side: Cultural Appropriation and Historical Erasure

This is the most adverse effect. The core good judgment of many misplaced civilization theories—that indigenous peoples (from the Egyptians to the Maya to the developers of Great Zimbabwe) couldn’t have created their very own monuments—is a form of highbrow colonialism. By attributing their accomplishments to a legendary out-of-place race (white, often Atlantean) or to aliens, these theories strip real, residing, or ancestral cultures of their records. They perpetuate racist 19th-century stereotypes that non-European peoples were incapable of class and complexity. This ancient erasure isn’t always just academic cheating; it’s a profound injustice that continues to shape how those cultures are perceived and valued today.

6. A Timeless Mirror – What Our Obsession Really Reveals About Us

Ultimately, the have a look at misplaced civilizations is much less an archaeological pursuit and more an exercise in collective psychology. These stories are a feature of a cultural Rorschach test, revealing our present-day anxieties and aspirations.

6.1 Anxiety About Our Own Collapse

In an era of weather alteration, rising sea levels, and geopolitical instability, the story of a prosperous civilization worn out by environmental catastrophe feels a lot less like an ancient delusion and more like a cautionary prophecy. Atlantis will become a photograph of our personal potential fate, a way to process our deep-seated fears about the fragility of our complicated world. The fantasy lets us play out the drama of disintegration in a secure, symbolic area.

6.2 The Eternal Search for Meaning and Origin

At its innermost level, the Atlantis Complex speaks to a fundamental human quest. We yearn to understand our origins. The ambiguous, incomplete report of prehistory is frustrating. Lost civilization myths provide a narrative of origin that feels epic, significant, and grand. They tell us we are the children of giants, that greatness is in our blood, and that our record is one of sublime success and tragic loss. It’s a more romantically pleasant foundation tale than the sluggish, laborious, and collaborative technique of actual human cultural evolution.

Conclusion: Embracing the Myth, Respecting the Truth

Our journey through the Atlantis Complex exhibits a multifaceted obsession. We’ve seen its start in Plato’s ethical allegory, its transformation into literal history, and its deep roots in our psychological want for golden long-term, clean motives, and dramatic narratives. We’ve mapped its sibling myths and watched it morph into pseudoarchaeology and ancient astronaut theory. We’ve acknowledged its strength to encourage exquisite artwork and its risky ability to erase actual cultural achievements.

The key takeaway is to understand the parable without conflating it with history. The story of Atlantis, and all misplaced worlds, is an effective piece of cultural storytelling. It is a reflection that displays our fears of the future, our nostalgia for an idealized beyond, and our eternal wrestling with the question of human capability. Its price lies in its symbolism, its poetry, and its ability to ignite our creativity.

We can experience the parable even as championing the fact. We can marvel at the concept of Atlantis at the same time as standing in awe of the very real, or even extra exquisite, achievements of the historical Egyptians, the Maya, the Mesopotamians, and all our ancestors who built the sector with their very own fingers, minds, and collective ingenuity. The actual lost civilizations aren’t people who sank below the sea, but the countless rich human tales that have been forgotten over time. Our fascination should drive us no longer to invent fictions, but to uncover, with rigor and respect, the astounding reality of our shared human past. In the end, the most compelling story is the true one.

A really good blog and me back again.