We learn that history is narrative. It is the master tale spun from chronicles, carved into stone, written in textbooks, and saved in national archives. We see it as an unbroken thread, tying together the past and the present in a rational, if occasionally chaotic, progression. But what if the maximum profound truths of our past aren’t determined in the noise of recorded occasions but within the quiet areas between them? What if history is taught now not handily by way of what is remembered, but also by way of what has been systematically, by accident, or tragically forgotten?

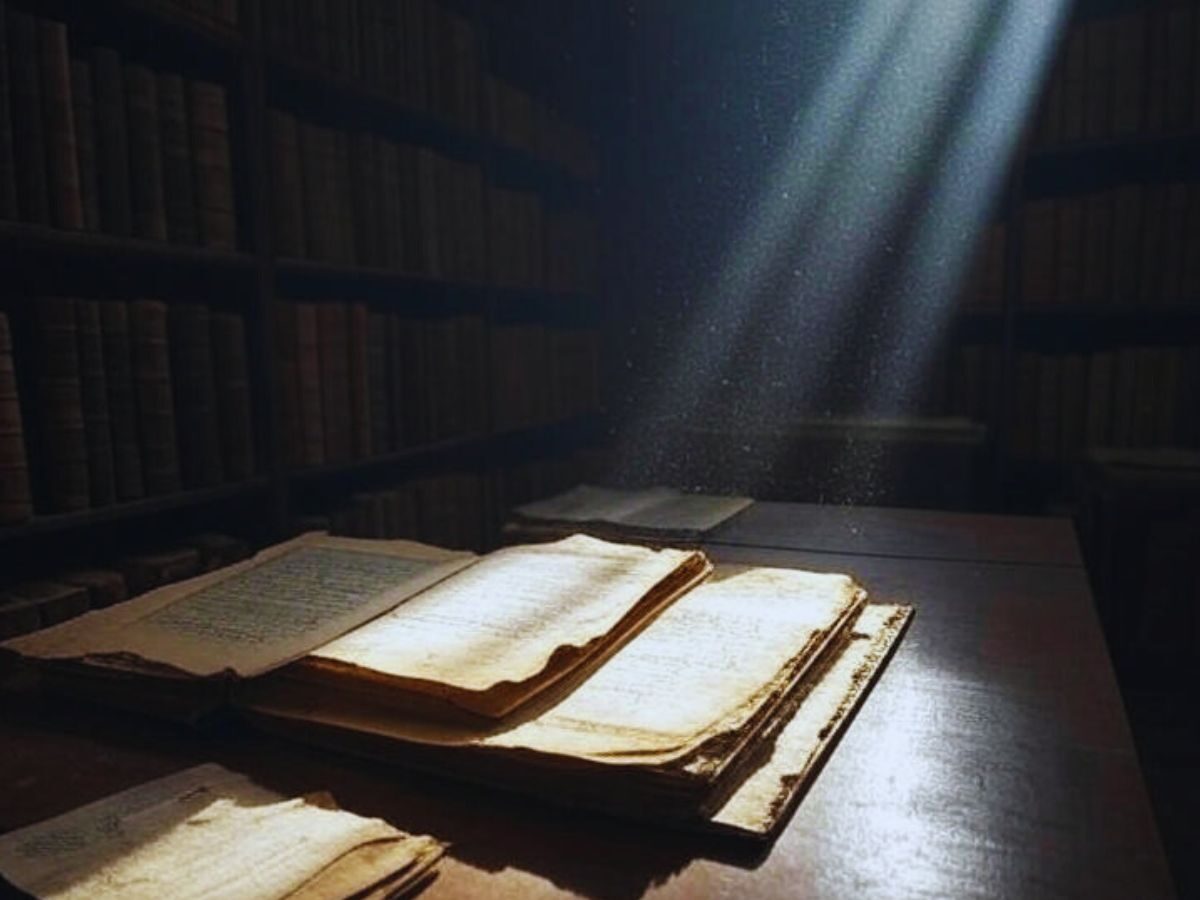

This is the world of historical silence—the amazing, regularly unsettling void in which reminiscence has faltered. To examine silence is to be an archaeologist of the unsaid, a detective of what has been overlooked. It is to understand that absence within the records isn’t a vacuity, however, an artifact weighted with meaning. By understanding how to read these memory silences, we break out of a flat perspective on the past and start to catch the faint, echoing whispers of those that history attempted to silence. This unspoken history reading is essential because it is in the silence that lies the deepest pain and the most enduring soul.

The Nature of Historical Silence: More Than Just Forgetting

First, we have to separate simple forgetting from historical silence. Forgetting is a passive activity; it is the natural decay of detail with the passage of time. We forget what we ate for lunch on a Tuesday three years ago. That loss is not significant to the larger fabric of human happenings.

Historical silence is not passive, though. It is an emptiness left by violence, by omission, by ideology, or by trauma. It is the redacted chapter, the missing name, the burned text, the stifled story. These intentional omissions in history are not errors; they are acts with effect. They determine our shared knowledge, frequently giving favor to one viewpoint while erasing another.

Imagine it more like a palimpsest—an old manuscript where the previous message was scraped off to give way to a new one. Even if the surface presents a new story, remnants of the previous, erased tale usually remain hidden underneath, only visible to those who know what they are doing. Our history is a palimpsest. The official record is the new text, but the ghosts of the unrecorded bleed through, and it is our task to interpret them.

The Many Architects of Silence

Silence in the historical record is not uniform. It is built by various forces, each imposing its own unique fingerprint upon the void.

1. The Silence of the Victors (and the Vanquished):

The most well-known saying, popularly ascribed to Winston Churchill, is that “history is written by the victors.” It is one of the chief causes of historical erasure. Conquerors take not only land and resources but also the story. They build monuments to themselves while demolishing those of the conquered. They write books that excuse their actions, portraying resistance as savagery and colonization as a noble mission to bring civilization.

But there is also a silence of the defeated. For groups who have suffered genocide, slavery, or cultural destruction, the trauma may be so extreme that it cannot be spoken. The experience lies hidden in the cultural memory, not as a narrative to be narrated, but as a burden to be borne. This is not an absence. It is a silence of depth—an armored wall around a wound too new. It is a form of mnemonic resistance, a means of preserving memory internally from the distorting eye of the oppressor.

2. The Silence of the Archival Gatekeepers:

History, up until a relatively recent past, was written down mostly by a thin slice of society: the literate, the wealthy, the male, and the powerful. Their worries, their land grants, their lawsuits, and their philosophical writings dominated the files. The lives of the far greater number—the peasants, the craftsmen, the women, the children, the slaves—were considered not worth writing about. Their birth, death, loves, and toil were the unremarkable context behind the “significant” activities of kings and soldiers.

This creates a profound archival absence. We know more about the tax policies of a medieval king than we do about the daily hopes and fears of the millions who lived under his rule. To find them, historians must become creative, reading “against the grain” of documents. A trial record about a stolen loaf of bread becomes a window into the desperation of poverty. A ship’s manifest listing human cargo as “goods” reveals the brutal mechanics of the slave trade. The silence is everywhere, but the keen eye can find the echoes of lives lived within the cracks of the official record.

3. The Silence of Trauma:

Maybe the most intricate silence is one born out of deep psychological trauma. For victims of atrocious events—war, genocide, rape—the memory may be so devastating that the mind shuts it out. The narrative breaks up, becomes non-linear, or is altogether unavailable. This personal experience ramps up to a public level, forming a generation of silence where the suffering of the parents is sensed but not known to the children.

This is not a silence of choice but one enforced, a breakdown of language in the face of the unimaginable. The event is a black hole in the family or national narrative, pulling everything toward it with its gravity even as its core remains dark and unsaid. The act of shattering this silence is a fine one that requires vast amounts of trust and moral delicacy, lest we intrude on hallowed spaces of suffering.

Listening to the Silence: The Methods of the Historian-Detective

If so much of history is defined by what is missing, how do we possibly recover it? This is where the historian transforms from a mere storyteller into a detective, a psychologist, and an artist. The process of silence remediation involves several key approaches:

1. Reading Against the Grain:

This is the major tool. It means taking a document produced for one reason and questioning it for something it was not intended to say. A slave owner’s journal, carefully logging weather and harvests, may casually refer to the illness or defiance of one slave. To the writer, it was an inconsequential aside; to the historian, it is a crucial hint about someone whose own voice was systematically repressed. We search for the shadows of invisible presences.

2. Turning to Alternative Sources:

When written records fail, we must look elsewhere. This is where material culture analysis becomes essential.

Archaeology: The grave goods, foundations, and trash pits of commoners have a tale to tell that written records too often neglect. The leftovers of a meal, the fashion of a piece of ceramics, the organization of a house—all convey loads about economic level, cultural activity, and daily life.

Oral Histories: In some strong oral cultures, or in some families, history is transmitted from generation to generation. Though they may evolve, they preserve the emotional truth and the vision of the people who were excluded from the written record. They are an important means of recovering silenced histories.

Art, Music, and Folklore: A spiritual, a folk tale, a quilt pattern, a protest song—these are all memory repositories. They store the hopes and fears, the history of a people, in a format that will endure even the most violent efforts at erasure of culture.

3. Embracing Toponymy and Linguistics:

The names we bestow upon places are striations of history. A street called “King’s Road” reveals one story. A mountain, given its name centuries ago by its original inhabitants, speaks another, frequently overwritten one. Toponymy, the history of place names, can uncover the cultural and linguistic strata of an area, pointing to populations displaced or assimilated but whose existence remains in the very words we employ to make sense of the world. Equally, those words incorporated into a language from elsewhere tend to indicate cultural exchange, trade, or conquest that is not necessarily well recorded somewhere else.

4. Acknowledging the Reflexive Turn:

Modern historiography also involves a crucial element of self-reflection. Historians now must ask themselves: What are my own biases? What silences am I, as a product of my time and background, likely to perpetuate? This historiographical metacognition is about being transparent about the limits of our own seeing. It admits that a complete history is impossible, but a more honest and inclusive one is not.

Case Studies in Silence: The Unspoken Shaping the Spoken

In order to make this tangible, let’s take a look at a few instances in which listening to silence has fundamentally transformed our knowledge of the past.

The “Dark Ages” That Weren’t:

The very designation “Dark Ages” for the epoch after the decline of the Western Roman Empire is a deep instance of periodization silence. It was invented by Renaissance scholars who regarded their own time as a revival of classical illumination and had the preceding centuries in mind as being a time of intellectual darkness and cultural ennui. This designation generated a silence that lasted centuries, deeming an entire era to be unworthy of scholarly scrutiny.

Today’s historians, by hearing this silence, have totally reversed this opinion. By seeing past the handful of extant Latin writings to archaeology, local law codes, and paintings, they’ve uncovered an era of phenomenal dynamism, creativity, and cultural blending. It wasn’t a “dark” age by any means; it was an age whose light simply passed through a different prism, one that previous scholars would not view through. Silence here was judgment, and to break it took a new question set.

The Silences of Slavery:

The archive of transatlantic slavery is a masterclass in deliberate historical omission. It is mostly written by and from the point of view of the enslavers: ship logs, ledgers of sale, plantation manuals, and political tracts arguing for slavery. The enslaved people’s own voices were silenced, their humanity erased by a system that characterized them as property.

To reclaim these voices, historians have had to be dogged. They dig through court files for freedom petitions. They interpret advertisements for fugitive slaves, which, often including detailed descriptions of physical appearance and abilities, humorously record a history of individual identity meant to lead to capture. And most importantly, they look to the few precious accounts written or dictated by enslaved individuals themselves, such as those of Olaudah Equiano or Frederick Douglass. These are not stories; they are acts of Herculean bravery, shattering a life of violent silence to declare one’s own humanity in the face of a system that is meant to snuff it out. Slavery’s silence is a deafening one, but when the whispers that cut through are some of the most potent in all human history.

The Untold Stories of Women’s Work:

For thousands of years, women’s work has been the unseen force of society. Their domestic labor—child-rearing, cooking, cleaning, spinning, healing—was “natural” and therefore unnoticeable, not infrequently worthy of official recording. This left an enormous gendered archival void.

Historians have filled this gap by examining wills that bequeath kitchen tools, looking at recipes passed down through generations, studying the bones of women for signs of repetitive labor, and analyzing the economic accounts of monasteries and great houses where women’s production was vital. The story of human progress is not just one of public inventions and battles; it is equally a story of the private, unpaid, and unsung labor that made all else possible. Listening to this silence forces us to redefine what we consider “historically significant.”

The Ethical Weight of Breaking Silence

Engaging with historical silence is not a neutral academic exercise. It is an ethical endeavor fraught with responsibility.

Who has the right to tell a story? Should an outside person try to re-create the story of a marginalized group, or is that just another kind of appropriation? The best is always to collaborate and to place the voices of the community themselves at the center, whenever feasible.

What are the consequences of speaking? For communities living with intergenerational trauma, unearthing buried memories can be re-traumatizing. The process must be guided by the needs and pacing of the community, not the curiosity of the researcher.

Can we ever truly know? We have to respectfully acknowledge that some silences will never be broken. Some things will be lost to us forever. Some of the work is being responsible for that loss, recognizing the limit of our knowledge, and making a history that is honest about its own gaps.

Conclusion: The Unfinished Symphony of the Past

History isn’t a closed book. It is an incomplete symphony, and the silences between the notes are as critical as the notes themselves. The areas in organizational memory aren’t blank; they’re full of witches, meaning anxiety and unstated stories. To practice records is to concentrate cautiously, no longer merely on the boisterous assured tunes of the effective, but on the faint rhythmic gasps of the unseen, on the reverberations of the songs that have never been written.

By tuning our ears to historic silence, we aren’t simply filling in gaps inside the narrative. We are merely changing its person. We transition from a record of actuality to a record of humility, from a history of statistics to a record of what that means, and from a history that glorifies to a record that is aware.

The paintings are huge and limitless. Each time we destroy a silence, we possibly locate another lurking below it. But in this cycle of endless exploration, we move closer to an extra sincere, a more compassionate, a greater entire know-how of the human route—a course whose fact resides as much in what is whispered as it does in what’s bellowed, and as much in what is recalled as in what’s, and is to stay, achingly, misplaced.

+ There are no comments

Add yours